This text has been translated into Bangla by Him Uddin, a resident of Venice and a research associate to the project, and is available here.

*

The Bangladeshi community in Venice is hard to miss, yet they remain completely invisible to most. Anyone who has visited Venice has seen them—perhaps not spoken to them, but certainly seen them. Venetians, tourists, and Bangladeshi immigrants constantly encounter one another, yet rarely interact. In my forthcoming book project, Banglascapes of Venice, I aim to make the lives and biographies of Bangladeshis more legible for Venetians and the millions of tourists who visit the city every year.

I am a Lecturer in Social Anthropology based at UCL, London, working at the intersection of conservation, climate maladaptation and migration. For the past decade, I have been conducting research with coastal residents living alongside the Sundarbans forests that straddle India and Bangladesh of the Bengal Delta. My research explores residents’ relationships to their land-water ecologies in the context of conservation and climate adaptation regimes. My research also explores the risks and hazardous work undertaken by these same coastal residents when they migrate to work in cities, factory shop floors and construction sites.

A workshop on waterways at Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, which compared the Venetian lagoon to the Bengal Delta, serendipitously led me to explore a well-known yet under-researched entanglement between Venice and Bengal. Both Venice and the Sundarbans are UNESCO World Heritage Sites and act as microcosms of the global ecological challenges the world is facing. Venice, like many other urban and rural centres in Italy, is also home to a large community of Bangladeshi immigrants. Fiction writing, such as Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island, the film Bangla Venice, and the environmental NGO We Are Here Venice founded by Jane da Mosto, acknowledge this entanglement of Bangladeshis in Venice. Yet little is known of their (watery) crossings, their hardships, homesickness, aspirations, and motivations to leave Bengal for Italy. Equally little is known of the labour they undertake, what they do for leisure, and their practices of grafting a home, work, and community in Italy.

My book seeks to make visible these otherwise invisible lives and to disaggregate what is by now a large and diverse community of Bangladeshi men, their wives, children, and parents from a range of districts including Kishorganj, Shariatpur, Comilla, Madaripur, Noakhali, Khulna, and Barisal. Some members of this community arrived in the early 1990s; they are homeowners with deep roots and relations to Italy. Their children are now adults who speak better Italian than Bangla. Others are new entrants, having just arrived in the country—often via Libya and Lampedusa on boats—risking their lives, undocumented, but with dreams for a better future in Italy.

As racialized imaginaries create panic about impoverished brown and black bodies from the Global South washing up at the shores of Europe (and the United Kingdom), through the microcosm of Venice, my book reveals the ways in which Italy depends on these very bodies for labour. Members of the Bangladeshi community work as waiters, dishwashers, and chefs in restaurants; they work as receptionists, room service staff, and cleaners at hotels. They work as seasonal agricultural labourers in farms neighbouring Venice. Approximately 4,800 Bangladeshi men work in the Fincantieri in Marghera, a world leader in building cruise ships, military ships, and customised vessels. If an older generation of Bangladeshi immigrants sell souvenirs and roses to tourists, the next generation are in university studying law, architecture, and undertaking PhDs in medicine.

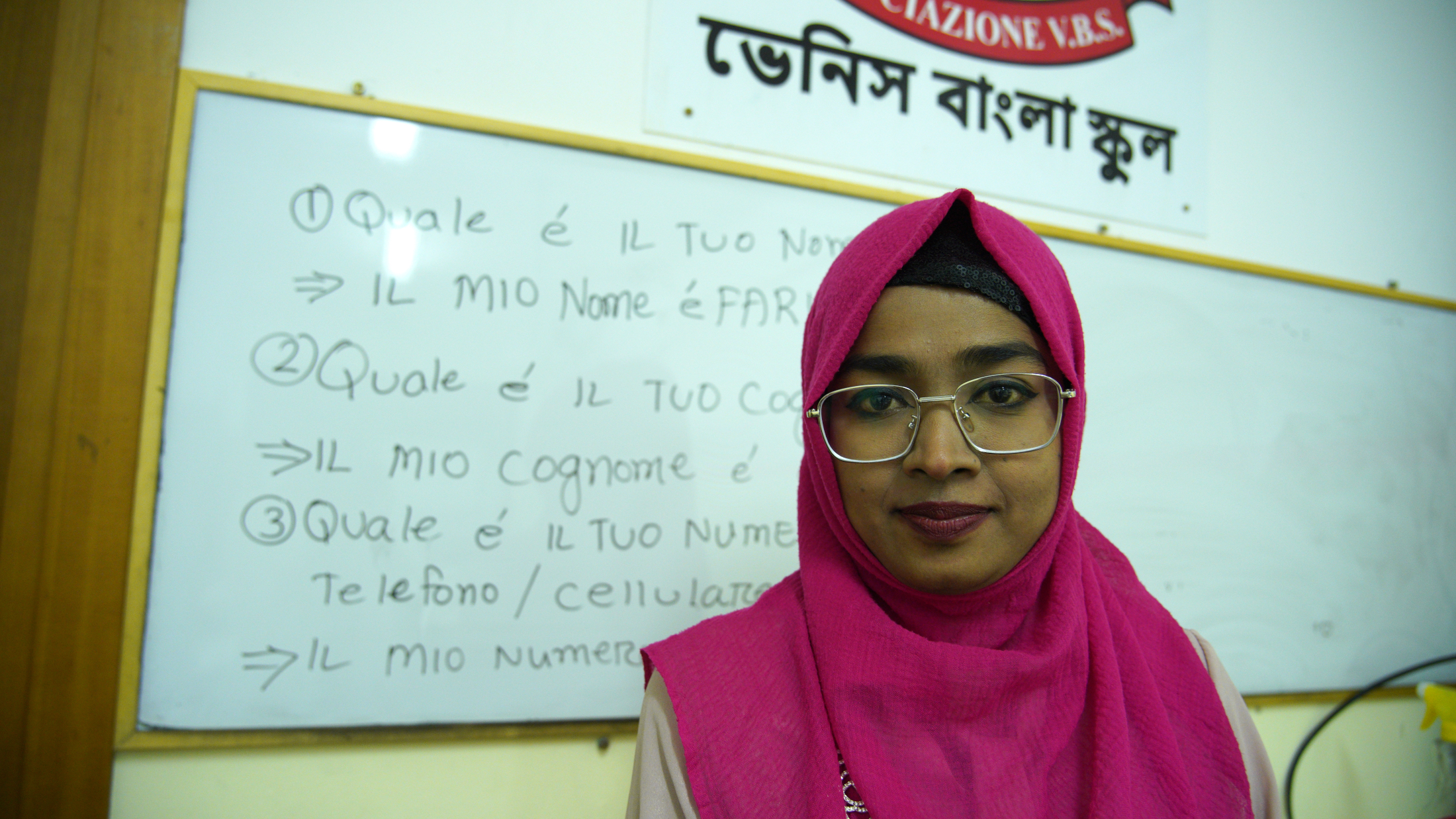

Banglascapes in Venice takes readers to several different land/waterscapes and sites around the city. These are spaces of labour and leisure; public, private, and clandestine; rural, urban, and intertidal. We travel from cricket fields to Venetian kitchens, farms that grow Bengali vegetables to mosques, hospitals, schools, and burial grounds. I spend time in the offices where migrants navigate the labyrinth of paperwork necessary to work and live in Italy, while also following a tiffin service that provides home-cooked Bengali meals to workers in Venice. The book features a self-organised community school—where second-generation Bangladeshi children, born in Italy, learn how to speak, read, and write Bangla, and newcomers from Bangladesh learn Italian in evening classes. From the fundamental challenges of giving birth in a foreign country and the struggles around housing to the more mundane tensions involved in inter-cultural romances or the inter-generational differences in culinary sensibilities of Italians and Bengalis—equally proud of their food traditions—Banglascapes of Venice represents a reality that is both specific to Venice while being prevalent in different shapes and forms across Italy and Europe. The book also acts as a reminder that Venice, a historically significant port city, has had several communities pass through it for centuries. It showcases the cosmopolitanism of Venice, not just through its biennales but also through its immigrant communities.

The ambition of my book is to make visible a population that is seen yet unseen, known yet unknown—a part of the daily life of Venice that produces and reproduces it, yet remains entirely segregated and often unacknowledged. My book is based on rigorous academic research, steeped in ethnography in both Venice and Bangladesh, but written accessibly for a wider audience interested in the intersecting challenges of migration, integration, identity politics, labour, and social reproduction—as these themes unfold in an increasingly warming world where both Venice and Bengal are emblematic of the ongoing emergency of climate change and authoritarian politics.

Alongside the book, I am also working with an award-winning documentary filmmaker and researcher Faiza Ahmed Khan to produce a series of short films on the entanglement between Bengal and Venice. Faiza is interested in community media and archival practices. Her previous documentary work around themes of migration includes Habitat 2190—a film with artist Hanna Rullmann—on how environmental laws are mobilised to direct the movement of migrants in Europe, in this instance, in Calais, where a nature reserve was built where a refugee camp once stood.

This book project is also committed to breaking silos in relation to environmental and political issues across vast geographical distances by revealing their entanglements. Social, political and ecological realities of the Bengal delta have been co-produced through histories of Empire and the region’s contemporary realities have an impact on Italy and Europe. Even as Venetians and Bangladeshis live in segregated worlds, their futures as well as those of their land-waterscapes are intertwined. To this end, the research of this book is committed to feeding into projects that create inter-connections and interrelations and will be conducted through collaborations and conversations with researchers at Ca ’Foscari University including Dr. Francesco Della Pupa, Dr. Francesco Vacchiano. Dr. Valeria Toniolo, and Dr. Pietro Omodeo as well as with a range of nongovernmental organisations including, We Are Here Venice and the Venice Bangla School.

For more information on the project, write to m.mehtta@ucl.ac.uk

Unless differently noted, all photo credits in this article go to Faiza Ahmed Khan.

Megnaa Mehtta’s book is scheduled for publication in early 2027.